Although we’ve had a French checking account for about a year, we’ve been exclusively using the account’s credit/debit card, the Carte Bleue, for in-person and online shopping. We have never bothered to obtain an actual checkbook from our bank in France. We very seldom used checks in the US because of the prevalence of online payments.

But, we recently had a need for a chèque issued on a French bank, so I set about acquiring a French checkbook called a Chéquier or a Carnet de chèques. I went online to BNP Paribas, our French bank, and searched for the link to order a Carnet de chèques. Of course, the website is in French and after stumbling around web pages for a good while using with my limited French language skills, I decided I needed some help locating the correct link.

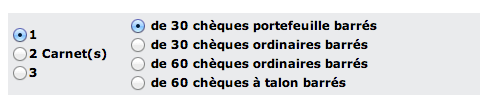

I “clicked in” to the BNP website’s “chat” function to “speak” with a bank representative who was extremely helpful. Totally embracing technology, I had one computer window open to the BNP website, a second window open to chat with the bank representative, and a third window opened to Google Translate to expedite the conversation with the French speaking bank rep. I worked through the online conversation and finally located the right web page to order chèques. However after reaching the correct webpage, I was offered the somewhat confusing options of:

While I understood the options of ordering 1, 2, or 3 carnets (books) of chèques with either 30 or 60 chèques each, I had to do some additional online research to figure out exactly what the differences were between chèques portefeuille barrés, chèques ordinaires barrés, and chèques à talon barrés. After visiting several online Expat forums I learned that:

Chèque portefeuille: has checks that are attached and tear away from the top like the majority of US checkbooks.

Chèque ordinaire: has checks that are attached to the left side like a book and tear away from the left side.

Chèque à talon: checks that are attached and tear away from the top, but with a”stub”(à souche) that gets left in the checkbook with a space for a personal memo.

Now understanding the options better, I selected the chèques portefeuille barrés (the choice most similar to what we have for our US checkbook) and “clicked” to have the Carnet de chèques mailed to us rather than the option of having the checkbook sent to our local bank branch for pick-up.

A week later, the Carnet de chèques arrived in the mail. First thing I saw was that French chèques are noticeably larger than US checks.

Also different from the US was a receipt included which had to be signed and returned to the bank acknowledging that the checkbook had arrived, there are no missing checks, and that the checks are printed correctly. Apparently the checks are not valid until the return receipt has been received at the bank.

There is a very specific formula to writing French checks. While US checks and French chèques look similar, there are several differences in their formats. The most obvious difference that a chèque written on a French bank is required to be written in French.

Line 1. “Payez contre cheque,” “Payez contre ce chèque‘,” or “Payez contre cheque non endossable.” The top line on US checks is where the payee’s name usually goes, so it’s important to know that “Payez contre cheque“ means “Pay against this cheque (this amount)” not “Pay to the order of” like is found on an US check. On the top line of the chèque you spell out the amount to be paid using French words. For example €87,50 needs to be spelled out as “Quatre-vingt-sept Euros et cinquante centimes” or “Quatre-vingt-sept Euros et 50/100 c.” I still struggle with understanding French numbers, but there are many “How to write a check in France” websites with “Numbers to French Words Converters” that look very helpful.

Line 2. “€” On this line the amount for the check is written in numbers. Remember that in France the comma (virgule) and the period (point) are used in writing amounts are reversed from the way the comma and the period are used in the US. For example: Two thousand eighty-seven Euros and 50 centimes is correctly written as €2.087,50 and not as €2,087.50.

Line 3. “A” This is the payee space that you write in the name of the person, company, or organization to whom the amount is being paid. A chèque for Mr. Dubois is written as M Dubois (for Monsieur Dubois), Mrs. Dubois as Mme Dubois (for Madam Dubois), or Miss Dubois as Mlle Dubois (for Mademoiselle Dubois.)

Line 4. “Fait à” or “A“. A departure from how checks are written in the US, on this line you write the name of the city of where the chèque is being written, for example “Fait à Carcassonne” or “a Paris.”

Line 5. “Le” This is the date line where today’s date is written. Remember that the European standard for writing a date is “day-month-year” (like the US military standard of writing dates.) A chèque written on Christmas day would be correctly written as 25-12-2014, not as 12-25-2014. Christmas day could also be correctly written as 25 décembre 2014. (The French do not capitalize the first letter of a month.)

| janvier = January février = February mars = March avril = April mai = May juin = June |

juillet = July août = August septembre = September octobre = October novembre = November décembre = December |

Line 6. Beneath lines 4 and 5 reading “Fait à Carcassonne le 25-12-2014″ is the space for a signature. There is often no actual “line” provided on French chèques for a signature like is usually found on US checks.

So now, with a Carnet de chèques in hand and understanding the format for writing a French chèque, we are finally ready to write that check.